Corridor 8 is a major axis for the development of the European continent. Corridor 8 is to connect the port of Burgas on the Black Sea with the Albanian coast of the Adriatic Sea via Northern Macedonia.

The war in Ukraine has further reinforced its strategic importance, but delays have been accumulating for two decades. This is stated in an analysis of the Italian Institute for the Balkans and the Caucasus, which the Bulgarian News Agency published without abbreviations.

"In my opinion, it is unlikely that Corridor 8 will ever be completed. I don't think the Russians will allow it. This is a game of political influence. Maybe they will allow a few goods to be transported, enough to mention the corridor here and there. But in reality it will all remain a dream."

So speaks not a logistics or international policy expert, but an ordinary worker at the port of Burgas, in one of the first scenes of "Corridor 8," a 2008 documentary that traces the route of the pan-European corridor, one year after Bulgaria joined the European Union.

Through individual stories, the documentary traces the route of Corridor 8, a road and rail infrastructure designed in the first half of the 1990s to provide an overland link between the Black Sea and Adriatic coasts through Bulgaria, northern Macedonia and Albania and on to the Italian ports of Bari and Brindisi.

Many of the stories in the film, often filled with witty Balkan irony, are still relevant today.

Whatever Russia's true role, Corridor 8 remains a puzzle whose pieces are waiting to be assembled.

Although some progress has been made, such as the recent opening of the Kumanovo-Beliakovce railway line in northern Macedonia, the overall vision of the project remains largely incomplete, especially in the cross-border sections of the countries involved.

As a result, the transport of people and goods from the Adriatic coast to the Black Sea, whether by road or rail, remains impossible or very complex, with travel times and infrastructure constraints making Corridor 8 an impractical and little-used option.

Officially, the completion of the corridor remains a priority for the governments of Sofia, Skopje and Tirana, as it is a tool for modernisation and cooperation that can bring tangible benefits to a region that has remained on the periphery of European economic development. However, the slow pace at which it is being implemented risks exhausting the project's potential.

In Bulgaria - a project still unfinished

Bulgaria, a member of the European Union since 2007, had to take the lead in the implementation of Corridor 8. In fact, much of the corridor's route through Bulgarian territory has been completed, both in terms of road and rail infrastructure.

In terms of overall functionality, however, the dream is still far from becoming a reality. Along the entire route, 52% of the road infrastructure and 55% of the rail infrastructure are located on Bulgarian territory. In the years following the country's accession to the EU, the main east-west road, the Trakia motorway linking Sofia with Burgas, was completed thanks to significant EU funding.

"As far as the rail network is concerned, work is currently underway to complete the modernisation of the Sofia-Burgas line," said Lyudmil Ivanov, an expert in rail transport management. "The line was supposed to be completed in 2023, but work has been delayed due to a number of factors, including difficulties in completing the longest tunnel on the route, which was built by a consortium of Turkish companies. However, it is realistic to expect that this section will be completed by 2029-2030, allowing trains to run at 160 km/h while ensuring modern safety standards," he added.

Once the line is completed, the journey between the capital Sofia and Burgas should take less than four hours, compared to the current six and a half hours.

However, the situation is not so rosy in the section that connects Sofia to the border with North Macedonia.

Here, the technical difficulties associated with the rugged, mountainous terrain are inextricably linked to the complicated political relations between Sofia and Skopje.

As far as the road connections are concerned, in 2022, there will be no road connections between Sofia and Sofia. The Road Infrastructure Agency has launched a procedure for designing a new highway from the Bulgarian-Macedonian border to the town of Dupnitsa, where it will connect to the existing Struma highway, which links Sofia to the Greek border.

However, no start date for the project has yet been announced.

Currently, the road connecting Sofia to the Macedonian border, passing through the towns of Pernik and Kyustendil, is classified as "level 1", i.e. as a long-distance rapid transit road. As far as rail links are concerned, the situation is even more complicated.

The section linking Sofia with Radomir is already electrified but needs major upgrading to bring it up to modern standards for transporting people and goods.

According to the 2011 project, the 72-kilometre stretch between Radomir and the Macedonian border is to be covered with a new route, which includes tunnelling and viaducts.

At the time, due to technical difficulties, the cost of the work was estimated at EUR 450 million - a sum that is likely to rise significantly.

"Given the current uncertainty about the availability of financial resources, it is difficult to predict when the work on the completion and modernisation of the Bulgarian line connecting Sofia with the Macedonian border will be completed," admitted Lyudmil Ivanov. At a time when the Black Sea has become a conflict zone due to the war in Ukraine, a logistical alternative linking the Adriatic and the Black Sea via NATO countries is crucial.

More than the mountains, however, the difficult political relations between Bulgaria and North Macedonia seem to be the main obstacles to overcome.

In 2017, with the signing of the Good Neighbour Agreement between then prime ministers Boyko Borissov and Zoran Zaev, the mood was optimistic. The agreement itself set 2027 as the target date for the completion of the railway line between Sofia and Skopje. Two years later, it was the current Bulgarian prime minister and minister of transport at the time who announced that by 2025, the train journey to the two capitals would take just one hour.

At the same time, Rosen Zhelyazkov confirmed Bulgaria's decision to focus on the road link between Dupnitsa and the border, but stressed that North Macedonia was not so interested in this chapter. "For us, the priority remains the rail link between Bulgaria and North Macedonia," Zhelyazkov concluded at the time.

However, it soon became clear that the promises would not be fulfilled in time.

In 2021, Bulgaria, North Macedonia and Albania signed a new tripartite protocol for Corridor 8: "This protocol precisely defined the routes and infrastructure to be built, and the deadline for final implementation was set at 2030.

"I am referring mainly to the doubts expressed by the government in Skopje, which in recent months seemed to question the priority of Corridor 8," he continued.

In January 2025, Sofia proposed to Skopje to sign an agreement for the design, construction and operation of a railway tunnel connecting the two networks at the Güeshevo-Deve Bair border crossing.

In March, however, the Bulgarian government announced changes to the Transport Connection 2020-2027 programme, abandoning plans to modernise the Sofia-Pernik and Pernik-Radomir sections, which were sacrificed due to financial constraints, in favour of completing the section leading to Burgas and the Black Sea, for which €500 million was initially allocated. "I believe that this decision is primarily technical, perhaps in order to optimise the implementation of transport projects and infrastructure included in European programmes. From a geostrategic point of view, however, I think this is the wrong decision," Hristo Alexiev said.

North Macedonia and Albania, far from being connected

The latest concrete progress along the corridor route has been made in North Macedonia, with the opening of the upgraded 30-kilometre Kumanovo-Belianovtse rail link to the border with Bulgaria, officially announced by Macedonian Prime Minister Hristian Mitkoski on 28 January 2025.

This section is only the first of a future 90 km line connecting Kumanovo to the Bulgarian border. Subsequent sections include Belakovce-Kriva Palanka (34 km) and Kriva Palanka-Deve Bair (24 km).

"The second section will be completed on schedule. In addition, we will tender the third section, which will allow us to be fully connected to our eastern neighbours," announced Christian Mickoski during his speech at the opening of the Kumanovo-Belianovce section.

Despite this major step forward, however, experts warn against making overly optimistic forecasts.

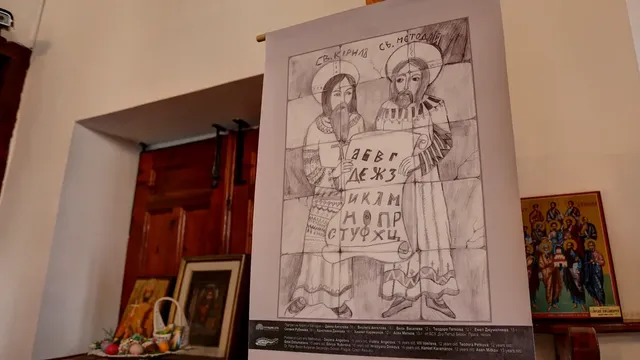

"The Kumanovo-Belianovce railway link was already built and had to be upgraded, as well as some bridges built, but this took more than a decade," explained Professor Zoran Krakutovski from the Railways Department at the Faculty of Civil Engineering of the University of St. Cyril and Methodius in Skopje. According to him, the slow progress of the work is due to bureaucratic delays, irregular tendering procedures and inadequate selection of contractors.

"If I could make decisions, I would choose reliable companies without improvising. The project is expensive anyway. But if we want it to be completed successfully, we must entrust its construction to serious companies. In particular, the 66 km long third section, from Kriva Palanka to the border, and the connected tunnel planned to cross the border with Bulgaria," Krakutovski added.

For now, it is extremely difficult to predict whether the section in question will be completed. Not to be forgotten, of course, is the work that is needed to move in the opposite direction, towards Albania, with the modernisation of the Skopje-Kicevo railway line and the work to connect it to the Albanian network.

Albania is currently the country where work on Corridor 8 is most behind schedule: the implementation of the project as a whole, according to Albanian journalist Gjon Rakipi, "is a festival of missed opportunities and systemic violations".

Completed works include the SH2 corridor linking Durres to Tirana and the A3 highway linking Tirana to Elbasan, completed in 2013.

On the other hand, the route linking Elbasan to the border with North Macedonia "remains beset by delays and unfinished work", while a key piece of infrastructure - Tirana's outer ring road - is still far from complete.

Albania's rail network, Gjon Rakipi commented, "is in an even worse state, an outdated relic of the twentieth century, with minimal commercial use and no functional cross-border links".

Beyond lack of resources, the root of the problem is governance: in Albania, many infrastructure projects are marked by mismanagement and accusations of corruption.

"The Tirana-Elbasan highway, for example, went 80% over budget, resulting in a €44 million fine after international arbitration. Disputes over land expropriation and sloppy environmental assessments add another level of dysfunction," said Gjon Rakipi.

Geopolitical competition

Corridor 8 was conceived primarily as a tool for economic development and regional cooperation: with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Black Sea becoming a conflict zone, geopolitical and strategic considerations may increasingly weigh on its future development.

According to Ardian Hakay, Director of Research at the Institute for Cooperation and Development in Albania, "Corridor 8 is currently receiving significant attention from the [Albanian] government and the EU, especially because of its security potential in Southeast Europe, which is receiving increased attention as a result of the war in Ukraine and the EU's reorientation towards defence and security."

"At a time when the Black Sea has become an area of conflict in recent years due to the war in Ukraine, I believe that a logistical alternative linking the Adriatic and the Black Sea through NATO countries is crucial," added Hristo Alexiev.

In addition to current concerns, there are longer-term strategic considerations and competitions. One of the oldest problems in the Balkans is related to the divergence of interests between the East-West axis, traditionally supported by Bulgaria, and the North-South axis, seen as an expression of the interests of Greece and Serbia, with North Macedonia being a vital pole for both systems.

It is therefore no coincidence that the current Corridor 8 (East-West) is seen by many analysts as a rival project to another corridor, Corridor 10, which crosses the Balkan Peninsula from north to south.

According to Hristo Alexiev, a new international player is now entering the fray: Beijing. In recent years, Beijing has visibly strengthened its position in the region, taking control of the port of Piraeus and financing a number of transport infrastructures to connect it to the rich markets of Central Europe.

"Serbia insists that Corridor 10 should be a priority. However, there is a risk that Chinese interests and investments will penetrate this axis as well. Beijing is currently building and financing much of Serbia's road and rail infrastructure through loans that create a subordinate relationship between Belgrade and China. So I would not be surprised if Beijing itself supported the desire to prioritise Corridor 10. Given the growing tensions over tariffs and logistics," the former transport minister pointed out, "it seems obvious to me that we need to think very carefully about which of these will prevail in the development of the region.

However, Lyudmil Ivanov, an expert used to the long planning timeframes for rail transport, points out that while the opportunities offered by the completion of a large-scale infrastructure are obvious, it is easier to predict which actors will be able to benefit specifically from them in the future.

"It is difficult to foresee the completion of the Corridor 8 railway before 2035-2040. We are talking about 10 to 15 years, which is an eternity in geopolitical terms. It took only a few weeks for the new US administration of Donald Trump to question many positions and alliances that were taken for granted until yesterday," Ivanov concluded. | BGNES

Breaking news

Breaking news

Europe

Europe

Bulgaria

Bulgaria