However, this is only half the story. Yes, cholesterol is a fat-like substance, and yes, it can be a problem... but not always. In fact, sometimes it is absolutely necessary.

"Cholesterol plays a key role in building cell membranes and is important for various hormones and other biological substances that keep us alive," says Sir Rory Collins, head of the Department of Population Health at Nuffield.

"However, the cholesterol levels we see, particularly in Western populations, are much higher than they should be."

That's where the problem lies. Its reputation as a fat that clogs arteries is confirmed when we reach dangerous levels. Blood clots, heart disease, and strokes are all linked to excessively high levels of cholesterol in the body.

According to the World Heart Foundation, high cholesterol is responsible for around 4.4 million deaths each year, and a 2022 study found that high cholesterol is the main risk factor for strokes.

Even more worrying is that in many cases, high cholesterol is asymptomatic – according to some estimates in recent years, up to 39% of people worldwide suffer from it without even knowing it.

"Most people don't get their cholesterol checked until they're in their 40s or 50s, and by then it's too late," says Steve Humphreys, professor of cardiovascular science at University College London. "Their arteries are already clogged with cholesterol."

So what can you do before it's too late? How can you protect yourself from something that is both extremely common and difficult to detect?

First, if you're concerned, talk to your doctor. Second, it helps to understand how cholesterol actually works. Here are the most important lessons modern science can teach us...

Reduce the right kind. The way we talk about cholesterol can give the impression that it's simply a matter of reducing it. But it's actually about achieving a good balance. Although problems associated with low levels are possible (a link has been established with anxiety, depression, and cancer), they are extremely rare.

Doctors consider a total cholesterol level below 5 mmol/l—that's a concentration of 5 millimoles per liter of blood—to be healthy. This applies to total cholesterol, but it is divided into two types.

You have probably heard that total cholesterol can be divided into "good" and "bad," but this is not entirely accurate.

The important thing to know about cholesterol is that it does not move freely in your body. Instead, it attaches itself to particles known as lipoproteins. These are special "trucks" that transport cholesterol and other fats through the bloodstream to different parts of your body.

What determines whether cholesterol is "good" or "bad" is not necessarily the cholesterol itself, but the role these lipoproteins play. Cholesterol is simply the "cargo."

There are two main types of lipoproteins. The first is low-density lipoproteins (LDL). These carry cholesterol from the liver, which produces most of the cholesterol, to various parts of the body, including the arteries.

This can be beneficial, but too much LDL that leaves cholesterol in the arteries can become a major factor in plaque formation. The LDL particles themselves can break down and stick to the artery walls—the more there are, the more likely this is to happen.

High-density lipoproteins (HDL), on the other hand, work in the opposite way. They are like garbage trucks that collect excess cholesterol from the bloodstream, including from the artery walls, and transport it back to the liver. This is why HDL cholesterol is known as "good" cholesterol.

The type of lipoproteins we have matters. We want to keep LDL levels low and HDL levels high. But how can we actively do that?

One of the most common misconceptions is that most of the cholesterol in our bodies comes from the food we eat. It is true that some foods, especially animal products such as meat and dairy products, contain cholesterol. However, most of it is produced by the liver (this is called "blood cholesterol").

The liver actually produces enough to supply the body with all the nutrients it needs. In fact, only about 20% of the cholesterol in our bodies comes from food—the rest is produced by the body.

What does all this mean for controlling cholesterol levels? First, the obvious: limit cholesterol in your diet to a minimum. After all, it just adds to the cholesterol already in your body.

"The best way to lower your cholesterol through diet is to avoid animal fats—dairy and meat. Other foods also contribute to cholesterol levels, but to a much lesser extent," says Collins.

Second, think of foods that can affect liver function as more like medicine than food. Even if they don't add cholesterol directly to the body, they can do so indirectly by stimulating the liver to produce more cholesterol.

Worse, more LDL than necessary may be produced, sending more cholesterol-laden cargo to your arteries.

Excess animal fats, especially fatty cuts, can lead to this effect. But one of the biggest culprits here is saturated fat. Deceptively, saturated fat can disrupt the function of receptors that help the liver keep total LDL in check.

Which foods should we point the finger at? Due to their saturated fat content, foods such as tropical oils (palm or coconut oil), baked goods, sweets, and fried foods contribute to raising "bad" cholesterol.

Processed meats—such as sausages, bacon, and hot dogs—also contain large amounts of saturated fat.

Then comes sugar. It also acts like a drug on the liver, stimulating it to produce more LDL and less HDL.

So, what's the solution? If you already eat a lot of these foods, reducing saturated fats and sugary foods will have the greatest effect. But what you replace them with can be crucial.

Fiber-rich foods are an excellent substitute. These include oats and whole grains, nuts, seeds, legumes, and beans.

Replacing your morning bacon sandwich with oatmeal can significantly help lower LDL cholesterol in several ways. Foods rich in soluble fiber (such as oats or whole grains) can bind to cholesterol in the small intestine, preventing it from entering the bloodstream.

Healthy fats, such as those found in salmon and sardines, are rich in omega-3. They have an effect on increasing the size and density of LDL cholesterol particles, making them less likely to stick to artery walls. Omega-3 can also signal the liver to produce more HDL.

Consuming these foods can help you control your cholesterol. However, the effect may be minimal. When it comes to your diet, the key is to focus on reducing unhealthy fats.

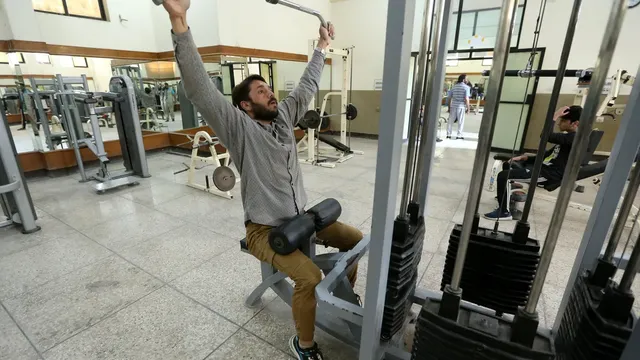

Another way to lower cholesterol is through physical activity. Cardio exercises have long been a key part of prevention.

As a review of 39 studies shows, aerobic exercise can significantly improve HDL levels. It turns out that by reducing inflammation, such workouts can create conditions that stimulate the production of particles that cleanse cholesterol in the body.

In addition, recent studies show that the more active you are, the more saturated fat your muscles use for energy. This means that less saturated fat circulates in the body.

"Higher HDL levels help balance total cholesterol, which, along with improving heart muscle and preventing obesity, helps prevent cholesterol-related health problems," says Humphries.

But it's not just about cardio. Research shows that strength training is also important — a 2012 study showed the effectiveness of weight training in lowering LDL. The more weight you lift, the greater the effect may be.

In some cases, exercise and a good diet aren't enough. Other hidden factors may play a bigger role in cholesterol levels.

First and foremost is age. As we get older and our liver function declines, the risk of high cholesterol increases.

While diet and physical activity can control cholesterol levels in most people, with age or in some rare cases where genetic disorders increase the risk, this becomes more difficult. In these cases, medication may be necessary (consult your doctor if you have any concerns).

The main medication used to treat high cholesterol is statins. They work by slowing down the production of cholesterol in the body by binding to a specific enzyme in the liver.

Statins are prescribed when a person's risk of cardiovascular disease or stroke becomes dangerous. Or, more commonly, to anyone who has already had a heart attack or stroke.

Although statins theoretically reduce the amount of cholesterol produced by the body, they have side effects. These can include headaches, dizziness, muscle pain, and fatigue.

"Muscle problems can occur, especially with older versions of statins. Approximately 1 in 10,000 people, usually during the first year of treatment, experience this effect, so it is rare," says Collins. "Since doctors are required to inform patients about this risk, people tend to attribute muscle pain to the medication."

"We know from placebo studies that in most cases when people report muscle pain, it is not caused by the medication. Statins are also associated with a very small increase in the risk of developing diabetes. This is mainly a problem for people who are on the verge of developing the disease, but the risk is small."

Collins emphasizes that when it comes to cholesterol problems, the best approach is individual—your needs may differ from those of others. Although medications carry a higher risk than exercise and diet, the benefits significantly outweigh the risks in serious cases. | BGNES

------------------

Alex Hughes, BBC Science Focus.

What actually causes high cholesterol (and how to lower it)

BGNES

Cholesterol has a bit of an image problem. The substance that circulates in our bodies has been demonized as a dangerous fat that clogs our arteries and potentially puts us at risk for heart disease and stroke.

Breaking news

Breaking news

Europe

Europe

Bulgaria

Bulgaria