Our planet may seem well-studied, but scientists warn that we have barely scratched the surface of Earth’s biodiversity. According to researchers, around 90% of all species on Earth remain unknown — a hidden world scientists call “biological dark matter.”

“For the vast majority of species, we don’t know what they are, where they live, or what they do,”

says Emily Hartop, taxonomist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

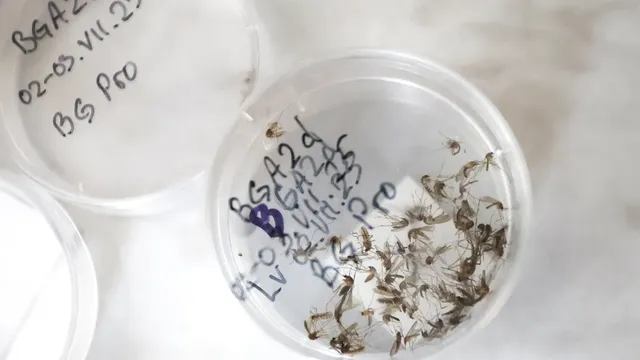

These “dark taxa” are mostly tiny insects, mites, and crustaceans, many of them less than 5 millimeters long. Unlike well-known animals such as elephants or bears, these species live in the shadows — yet they are vital for ecosystem balance, including soil formation, pollination, and maintaining food chains.

The scale of the unknown is astonishing. Scientists estimate there could be 1.8 million species of certain small flies alone, but fewer than 7,000 have been described. In just one year of insect trapping in Los Angeles, Hartop’s team discovered 99 new species of Phoridae flies — 43 previously unknown. In Singapore, out of 120 species collected, only five were already documented. And in Costa Rica, over 400 of 416 parasitic wasp species remain undescribed.

The DNA Revolution

Until recently, cataloguing this hidden diversity seemed impossible. But DNA sequencing has transformed the field. Through genetic barcoding, scientists can now distinguish thousands of species simultaneously, even when they look almost identical under a microscope.

“Thanks to DNA barcodes, we’ve entered the golden age of biodiversity discovery,” says Paul Hebert, founder of the “Barcode of Life” project.

Launched in 2005, this international initiative aims to map the genetic code of every animal species on Earth. Hebert believes that with about $1 billion in funding, humanity could complete the biodiversity inventory by 2040 — an unprecedented scientific milestone.

Understanding this hidden life is more than curiosity; it’s a necessity. Cataloguing Earth’s biodiversity helps scientists track evolution, detect pathogens, prevent food chain disruptions, and protect ecosystems.

As Hebert concludes: “This is the planet we live on. We must understand the organisms we share it with.” | BGNES

Breaking news

Breaking news

Europe

Europe

Bulgaria

Bulgaria